Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a form of ocular inflammation that involves the peripheral portion of cornea and may be associated with systemic conditions such as Rheumatoid Arthritis(RA), Wegener’s Granulomatosis(WG), and other systemic conditions. It is a potentially devastating disorder consisting of a crescent-shaped destructive inflammation at the margin of corneal stroma that is associated with an epithelial defect, presence of stromal inflammatory cells, and progressive stromal degradation and thinning.

The onset of Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis has been linked to various anatomical factors of central and peripheral cornea and adjoining limbus. Though the local concentration of small and medium weight proteins like IgA, IgG and most complements are similar in central and peripheral cornea, the peripheral cornea has been found to be associated with higher concentrations of higher molecular weight(HMW) protein molecules like IgM and complement C1(5 times), possibily owing to tight arrangement of corneal lamellae. The Peripheral cornea is also known to harbour reservoir of various inflammatory cells like neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and mast cells and antigen presenting Langerhans dendritic cells, which is present only in conjunctiva and peripheral cornea. Besides, the peripheral cornea is also supplied by capillary arcades (supply peripheral 0.5 mm cornea).

The major pathophysiologic mechanism is a result of degradation and tissue necrosis of corneal stroma produced by degradative enzymes, which are released primarily by neutrophils attracted into the area by diverse stimuli.

The etiology of PUK may broadly be divided on the location and extent of causative factor as ocular (localized) and systemic(Table 1). Further the above two can further be classified on the nature of inciting insult as infectious and non-infectious.

Approximately half of the etiology of PUK is catered by autoimmune vasculitic disease (endothelial injury), attributed to deposition of immune complexes on vascular endothelium or leucocyte mediated cytotoxicity caused by antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) directed against neutrophil granule enzymes mainly antiprotease-3 and antimyeloperoxidase (ANCA positive pauci-immune vasculitis). Autoimmune vasculitis may manifest variably as PUK, necrotizing scleritis, Keratitis, retinal vasculitis and optic neuropathy.

Whatever may be the etiology, the final common pathway consists of release of proteolytic and collagenolytic enzymes from inflammatory cells. Early diagnosis and treatment of peripheral Keratitis may be important in altering the prognosis of the ocular and also a possibly life threatening systemic disease.

|

Etiology |

Infectious |

Non-infectious |

|

Ocular |

|

|

|

Systemic |

|

|

Table 1: Etiology of PUK

PUK produces great morbidity from the pain and resultant visual disability. It can be a harbinger of death if the underlying disease is not diagnosed and successfully treated.

Clinical Examination

As PUK is frequently a manifestation of occult systemic disease, a thorough systemic history is very important and should include chief complaint, characteristics of present illness, past medical history, family history, and a meticulous history of systemic diseases.

Symptomsare quite variable but nonspecific foreign body sensation with or without eye pain, watering, photophobia, and reduced visual acuity are the most common.

Eye pain may be pronounced in PUK associated with autoimmune vasculitis like RA, WG, PAN, and RP often linked with scleritis and Moorens ulcer which has no scleral involvement, particularly if the latter is bilateral.

Clinical features

May be divided into systemic and ocular.

Systemic symptoms:There are a number of clinical findings which are elaborated in table 2.

Ocular features:

Appearance of corneal stromal ulceration with epithelial defect adjacent to the corneoscleral limbus with an intrastromal white blood cell infiltrate is a common finding. Clinical disease severity may be predicted by the depth of the ulcer (0-4+) and adjacent conjunctival inflammation (0-4+). The detection of scleritis, especially the necrotizing form is highly associated with systemic vasculitis.

Diagnostic tests and Systemic Review:

After a systemic review, a preliminary diagnosis of a few systemic syndromes appears. The specific diagnosis is achieved by combining the clinical diagnosis with a few confirmatory laboratory tests. Blanket investigations for PUK testing are not required.

Within the ANA (HEp-2 cell substrate) the detection of anticentromere antibodies (centromere-specific pattern) provides an important tool in the diagnosis of PSS, especially the limited cutaneous form (CREST syndrome: calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal hypomotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia).

Ocular tissue biopsy in suspected autoimmune PUK such as Mooren’s ulcer and systemic vasculitic syndrome-associated PUK can be very helpful in reaching a specific diagnosis and deciding a specific therapy.

The systemic review may provide important clues to the specific systemic diagnosis. The detection of saddle nose deformity and/ or auricular pinnae deformity, secondary to inflammation of the involved cartilage can be important clues to the diagnosis ofRelapsing Polychondritis(RP).Saddle nose deformity and/ or nasal ulcers can be a sign ofWegener’s Granulomatosis(WG).A butterfly rash across the nasal bridge extending to the malar areas and/or alopecia suggests the diagnosis ofSystemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Loss of facial expression and normal skin wrinkles associated with facial telengiectasias suggest the diagnosis ofProgressive Systemic Sclerosis(PSS).Erythema, telengiectasias, papules and pustules in forehead, cheeks, chin, and nose with and without rhinophyma can establish the diagnosis ofAcne Rosacea.However, this is not frequent in India. One case report documents peripheral corneal ulceration as the presenting sign of temporal arteritis.Tenderness and erythema of temporal artery suggest the diagnosis ofGiant Cell arteritis(GCA).

|

Systemic Diseases |

Clinical Finding |

|

RP, Wegener’s granulomatosis |

Saddle nose deformity |

|

RP |

Auricular pinnae deformity |

|

Wegener’s granulomatosis |

Nasal mucosai ulcers |

|

SLE, Sjog |

Oral/lip/tongue mucosal ulcers |

|

SLE |

Facial ”butterfly” rash ,Alopecia |

|

SLE, , RP |

Hypo/hyperpigmentation (scalp, face) |

|

G-C |

Temporal artery erythema/tenderness |

|

RA, SLE, Wegener’s granulomatosis, PAN |

Subcutaneous nodules in arms and legs |

|

All vasculitic syndromes |

Arthritis in arms and legs |

Table 2.Clinical findings in Peripheral Ulcerative Keratltis and suspected systemic disease

Ocular Investigations:include

-

Scraping and culture of the lesion to rule out underlying infection.

-

Conjunctival resection/biopsy may be helpful in removing the limbal source of collagenases and other factors causing progressive ulceration rather than any diagnostic finding.

|

Systemic Disease |

Laboratory Tests |

| Giant cell arteritis |

ESR, CIC, IgG, |

| Systemic lupus Erythematosus |

All of 1 +ANA (anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm), Cryog, C |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

All of 2 + RF and joint X-rays |

| Sjogren‘s syndrome |

All of 2+ RF, ANA (anti-Ro, anti-La), IgA, IgM, syalography |

| Polyarteritis nodosa |

All of 2 + HBsAg, angiography |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis |

All of 2 + RF, IgA, IgE, sinus and chest X-ray, BUN, creat clearance |

| Progressive systemic sclerosis |

All of 2 + RF, ANA (anticentromere, anti-Scl-70), |

Table 3.Laboratory Tests for Suspected Systemic Diseases

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; anti-dsDNA, antibody to double-stranded DNA; anti-sm, anti-RNP, anti-Ro, anti-La, antibodies to small nuclear ribonucleoproteins-Sin, -RNP, -Ro, and -La: CIC, circulating immune complexes; IgG, IgA. IgM, IgE, immunoglobulins: C, complement (C3, C4, CH50): Cryog, cryoglobulins; RF, rheumatoid factor: HBSAg. hepatitis B surface antigen: WBC, white blood count; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

Histologic Findings

In Mooren ulcer, corneal thickening occurs at the margin of the ulcer where inflammatory cells have invaded the anterior stromal layers. However, the inflammation is nonspecific, and no etiologic agent can be identified. Necrosis of the involved epithelium and stroma is seen. PUK associated with connective tissue disease and PUK associated with mild infections sometimes may appear similarly. Signs of vasculitis in the adjacent conjunctiva may be seen.

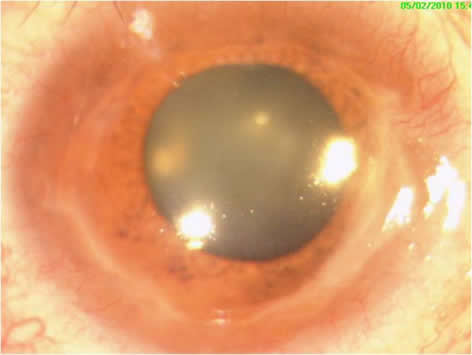

Figure1.Clinical Photograph showing 180 degrees peripheral corneal defect

Treatment:

The treatment of PUK is determined by the type and severity of the disease.

Systemic:

Systemic glucocorticoids are the cornerstone of therapy. Glucocorticoids are initiated at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day (maximum of 60 mg daily), followed by a tapering schedule based on clinical response. Patients in whom the loss of vision is imminent should be treated with pulse methylprednisolone, 1 gram/day for three days. If there is imminent danger of corneal perforation and in association with systemic vasculitis alkylating agents may be used in conjunction with glucocorticoids.

Cyclophosphamide (up to 2mg/Kg/day) in addition to high dose glucocorticoids may be given in non-responsive cases(Jabs 2005). As with scleritis, methotrexate up to 25mg/week, azathioprine up to 200mg/day, and mycophenolate mofetil up to 1g twice daily can be given.

The treatment of PUK with immunosuppressive medications is fraught with treatment-related morbidity and mortality. Patients on high-dose glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive agents require careful monitoring, with frequent check-ups and blood workups. Patients on cyclophosphamide should have a complete blood count checked every two weeks. Surgical resection of conjunctival tissue adjacent to PUK has been promoted as a means of decreasing access to inflammatory cells and factors to the peripheral cornea. However, it is controversial, as it is not uniformly agreed that resection alters the course of the disease. Surgical management of PUK is used in cases of impending perforation. Surgical options exist depending on the size of perforation such as the use of a tissue adhesive bandage contact lens, a lamellar graft, and tectonic corneal grafting.

Topical:

Topical therapy with antibiotics and steroids has been found to be useful in regression of the symptoms as well as healing of the lesion. Great caution should be taken in the use of steroids in rheumatoid marginal furrowing with epithelial defects and sterile keratolysis as the same may lead to hastened thinning and perforation. In steroid-refractory cases, cyclosporine 0.5% eyedrops may be undertaken after ruling out fungal and bacterial infection. Preservative-free lubricants are added for the management of the ocular surface.

Complications:

PUK may be associated with significant eye and systemic morbidity. In one retrospective review of 24 patients with scleritis associated PUK, all 24 patients had impending corneal perforation, 16 (67%) had associated anterior uveitis, and 20 (83%) had decreased vision, defined as a decrease in visual acuity of 2 or more Snellen lines at the end of follow up or visual acuity of 20/80 or worse at presentation. In another retrospective review of 47 patients with PUK, 34% had impending or frank corneal perforations (defined as peripheral corneal thinning of 75-100%), 47% required a tectonic graft procedure, 9% had associated anterior uveitis, and 43% had visual acuity of 20/400 or worse at presentation. In addition to the high risk of ocular damage from PUK, eye inflammation of this nature is a harbinger of active inflammatory disease in other organ systems with major potential for morbidity and mortality

Major systemic vasculitis:

Rheumatoid ArthritisPatients with RA vasculitis have high titers of rheumatoid factor, low serum complement, cryoglobulinemia, and circulating immune complexes. In addition, they may have a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anemia, thrombocytosis, and diminished serum albumin. Antinuclear antibodies (anti-RNP) also can be present.

Rheumatoid Arthritis is a generalized, chronic, inflammatory, and symmetric type of polyarthritis affecting nearly 3% of the general population and postulated to be the most common systemic disease associated with PUK. The diagnosis of RA is clinical with arthritis of three or more joints (especially proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, and wrist joints), morning stiffness, rheumatoid factor, and autoantibodies to IgG in the serum. Various etiologic factors have been ascribed to the disease process in the past like HTLV-1infection, growth of autoreactive T-cells polymorphic HLA like HLA-DRB1*0401, and IgM formation against patient’s IgG but the exact mechanism of the disease still remains elusive. Very high titers of IgM Rheumatoid Factor are typically present in active vasculitis.

Ocular manifestations include keratoconjunctivitis sicca, episcleritis, anterior scleritis, marginal corneal furrows, and choroidal lesions, and /or retinal vasculitis secondary to posterior scleritis as sever to scleral involvement like necrotizing scleritis and scleromalacia perforans (secondary to occlusive vasculitis).

The PUK in RA is mild to moderate in-depth (25 to 50% of corneal thickness), generally appears late in the disease, and usually heralds worsening of the systemic disease. The ulcer does not progress centrally and responds well to systemic NSAIDS in combination with systemic and/or topical steroids. High-dose pulse intravenous corticosteroids can be effective in rapid relief of disease until the slower-acting remitting agents take effect. Immunosuppressive agents like methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and the most recently used well-tolerated Mycophenolate mofetil have been found to have favorable results.

“Step down bridge model”of treatment involves initial treatment with fast-acting steroids and methotrexate to control inflammation, which is later replaced with disease-modifying agents(e.g.-hydroxychloroquine). In the“Sawtooth model”disease-modifying agents are started early and later replaced by such similar agents as each loses efficacy.

The primary therapy for severe PUK consists of aggressive control of inflammation bysystemic steroidscombined withimmunosuppressive medication, methotrexate (5-25mg once a week) as the initial immunosuppressive therapy in most cases. Topical steroids pose risk for aggravation of the ulcer and perforation hence are not routinely recommended.

Surgical procedures though important are mostly palliative and insufficient to prevent recurrences.Conjunctival resectionmay remove collagenase and interrupt local autoimmunity by access of mediating cytokines.Tissue adhesivesmay prevent access of inflammatory cells from an ulcer, and further damage. Conjunctival flaps and corneal grafts (lamellar, crescentic, or penetrating ) may be required to preserve the integrity of the globe. Keratoplasty carries a poor prognosis in PUK associated with RA owing to the recurrence of corneal melting and perforation in the graft.

Systemic Lupus ErythematosusThe presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), especially to native double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and to small nuclear ribonucleoproteins-Sm (anti-Sm) is very specific for SLE. Other ANA such as antibodies to single-stranded DNA (anti-sDNA) and antibodies to small nuclear ribonucleoproteins-RNP (anti-RNP), -SS-A (anti-SSA or anti-Ro), and –SSB (anti-SSB or anti-La), although present in SLE but are non-specific. The ANA pattern in SLE may be peripheral (rim), homogeneous, speckled, or nucleolar. Deep keratopathy and PUK are relatively infrequent compared to epithelial lesions in SLE, hence NSAIDS and antimalarial therapy (e.g. hydroxychloroquine sulphate ) may be sufficient therapy in most SLE cases.

Wegeners GranulomatosisThe presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), especially the termedc-ANCA(anti-p29 neutrophil protein) and abnormalities in sinus and chest x-rays are very specific for Wegener's granulomatosis. Although less sensitive for limited Wegener's granulomatosis, ANCA has been found to be exquisitely sensitive and specific in association with scleritis in various studies. c-ANCA have a specificity of 90% in the biopsy proven WG.

WG is multisystemic disease involving nectotizing vasculitis of upper and lower respiratory system and also renal system. The mortality rate is quite high. PUK is common and bilateral manifestation of WG. The ulcer usually starts as paralimbal infiltrates leading to epithelial and stromal necrosis and formation of subsequent furrow. The same may extend concentrically to form a ring ulcer or progress centrally. Ocular manifestations may be similar in both classic and limited WG except that remissions are more frequent in limited variant. Systemic therapy with Corticosteroids at a dose of 1mg/kg and immunosuppressive agents like cyclophosphamide at initial dose of 2mg/Kg (classic WG) or methotrexate (limited WG) may be both effective in achieving remission and reducing mortality. Corneal perforation may be treated with cyanoacrylate glue or conjunctival flap. A case report by Indie Friedlin et al has supported the role of rituximab (chimeric antibody against CD20 of B cells) in the treatment of PUK in a patient of WG refractory to all other treatment.

Relapsing PolychondritisRelapsing Polychondritis is a rare autoimmune disease with a predilection for involving various cartilaginous tissues(antibodies to collagen types II, IX, and XI detected) in the body thus causing systemic features like saddle nose, auditory impairment, and also potentially fatal cardiac conduction defects, aortic aneurysms, and laryngotracheal cartilage collapse. The most common ocular findings are episcleritis(39%) and scleritis(14%) followed by lid edema, iritis retinopathy, muscle edema, optic neuritis, and PUK(4%). Whereas topical steroids with systemic NSAIDs or dapsone is sufficient for mild diseases like episcleritis or mild scleritis, severe forms of sclerokeratitis like nodular or necrotizing scleritis generally require systemic steroids and /or cytotoxic agents. Rapidly progressing refractory PUK may require pulse intravenous steroid therapy and/or immunosuppressive treatment.

Polyarteritis NodosaThe presence of hepatitis B surface antigen, diminished serum complement, or cryoglobulinemia suggests the diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa(PAN). Polyarteritis Nodosa is a necrotizing vasculitis involving small and medium-sized vessels of the body. It is broadly categorized into four categories: microscopic or micro-PAN, classic PAN, allergic angiitis and granulomatosis (Churg Strauss syndrome), and an overlap syndrome of systemic necrotizing vasculitis. Diagnosis of PAN relies on histopathology of biopsied tissue from various systemic lesions like skin muscle and nerve. A wide variety of ocular manifestations may be seen in certain cases like orbital pseudotumor, papilledema or papillitis, and dysfunction of ocular movements. Conjunctival, corneal and scleral involvement is seen in vasculitis of the anterior ciliary artery. Combination therapy of high/normal dose systemic corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide have been found benefitting in reducing both systemic mortality and ocular inflammation. In hepatitis, B or C associated PAN systemic interferon alfa-2b (3 million units subcutaneously, three times per week for at least 6 months) therapy may be considered in treatment of PUK.

Moorens ulceror chronic serpiginous ulcer or “ulcus roden” was first described by Bowman in 1849 but was named after Mooren, who first published multiple cases of the disease. The exact etiopathogenesis remains uncertain but has been proposed to be autoimmune activation of both cell-mediated (local accumulation of neutrophils and other WBCs) and humoral immunity (disproportionate increase of helper T cells with a downfall of cytotoxic T cells) against specific corneal antigens(eg Cornea specific Antigen (Co-Ag), a calcium-binding protein of S-100 family) altered under the influence of systemic disease, trauma or infection (Martin). It may at times be difficult to differentiate from the PUK associated with collagen vascular disease. However incapacitating ocular pain out of proportion to inflammation, overhanging central corneal edge and absence of scleral involvement or systemic associations may be diagnostic of Moorens ulcer. The condition is usually found as chronic ulcerating Keratitis usually in the interpapebral area (usually medial and/ or lateral cornea) with circumferential and central spread involving half of the stromal thickness. The hallmark of the disease is the undermining of the irregularly scalloped central edge(overhanging central edge) giving a false impression of relatively less severity of the ulcer. Wood and Kauffman classified Mooren’s into two clinical types. Limited or typical one usually found unilaterally (75%) and in the elderly age group, presents with milder symptoms and good response to medical and surgical treatment while atypical or malignant variant is mostly bilateral (75%) may be found more commonly in younger age group and certain ethnic groups like Nigerian males, presents with rapidly progressing, a severe form of the disease and responds poorly to treatment. Treatment options include a stepladder approach with frequent topical steroids, generous conjunctival resection, systemic immunosuppressives, additional surgical procedures like superficial lamellar keratectomy, lamellar tectonic graft, crescentic patch graft, and glue application with the placement of BCL, visually rehabilitating keratoplasty.

References

1. MondinoBJ, Brady KJ: Distribution of hemolytic complement in the normal cornea. Arch Ophthal 99;2041-44,1981

2. Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Hoang-Xuan T, Foster CS. An analysis of therapeutic decision-making regarding immunosuppressive chemotherapy for peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Cornea. 1990;9(1):66–73.

3. Gerstle CC, Friedman AH: Marginal corneal ulceration limbal guttering as a presenting sign of temporal arteritis. Ophthalmology 87:1173-1176, 1980.

4. Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509–16.

5. Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS, Baltatzis S. Ocular characteristics and disease associations in scleritis-associated peripheral keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(1):15–9.

6. Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Hoang-Xuan T, Foster CS. An analysis of therapeutic decision-making regarding immunosuppressive chemotherapy for peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Cornea. 1990;9(1):66–73.

7. Koffer D The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis.Clin symptoms31:2125;1979

8. Brown SI, Grayson M: Marginal furrows: A characteristic corneal lesion of rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Ophthalmol 79:563-567, 1968

9. Foster CS. Immunosuppressive therapy for external ocular inflammatory disease.Ophthalmology87.140-50;1987

10. FederRH, Krackmer JH. Conjunctival resection for rheumatoid corneal ulceration.Ophthalmology;91:111-14:1984

11. Messmer EM, Foster CS. Vasculitic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43(5):379–96.

12. Mondino B, Brown S, Rabin, B: Autoimmune phenomena of the external eye. Ophthalmology 85:801-817, 1978

13. Messmer FM, Foster CS. Destructive corneal and scleral disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis.Cornea:14;408-417,1995

14 Nolle B, Specks U, Ludemann H, et al.: Anticytoplasmic autoantibodies: Their immunodiagnostic value in Wegener's granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med 111:28-40, 1989

15. Soukiasian SH, Foster CS, Niles JL, Raizman MB: Diagnostic value of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in scleritis associated with Wegener's granulomatosis. Ophthalmology 99:125-132, 1992

16. Mckenzie H: Disease of the Eye. 1854, p 631

17. Bowman W: Case 12, pll2 in The parts concerned in the operations of the eye (1849), cited by Nettleship E: Chronic Serpiginous Ulcer of the Cornea (Mooren's ulcer). Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 22:103-144,1902

18. Mooren A: Ulcus Rodens. Ophthalmiatrische Beobachtungen. Berlin, A. Hirschwald:107-110, 1867

19. Sangwan, P Zafirakis, CS Foster. Mooren's ulcer: Current concepts in management. Current Ophthalmology 1997:Vol 45,Issue 1;7-17