Retinal vasculitis is an inflammatory disease of the blood vessels of the retina that may be associated with primary ocular conditions or with inflammatory or infectious diseases in other parts of the body (systemic diseases). It has been defined as the vascular leakage and staining of vessel walls on fluorescein angiography, with or without the clinical appearance of fluffy, white perivascular infiltrates in an eye with evidence of inflammatory cells in the vitreous body or aqueous humor 1.

Typically, retinal vasculitis is divided into entities localized to the retina and into systemic diseases involving the eye. These include certain ocular disorders, systemic autoimmune disorders, and some infectious diseases.

Etiology:

The common primary causes of retinal vasculitis where vessel is the primary target of the inflammatory process are:

(a) Localized to the eye

- Idiopathic

- Intermediate uveitis of the pars planitis type

- Frosted branch angiitis

- Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis (IRVAN)(b) Involving the eye and other organs (primary systemic associations)

Giant cell arteritis

Takayasu arteritis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Wegener’s granulomatosisChurg-Strauss syndrome, Essential cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, and Cutaneous leucocytoclastic angiitis are some of the rare systemic associations.

The causes of secondary vasculitis (where vasculitis is a prominent feature but is secondary to an inflammatory process not primarily directed against the vessel) are:

(a) Localized to the eye:

-

Ocular sarcoidosis

-

Birdshot chorioretinoapthy retinal vasculitis

-

Necrotic herpetic retinopathies (herpes simplex, varicella zoster virus)

-

Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis

-

Tuberculosis

-

DUSN (Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis)

-

Primary ocular lymphoma

(b) Associated with systemic involvement

-

Sarcoidosis

-

Behçet’s disease

-

Multiple sclerosis

-

Systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE)

-

Spodylarthritis with HLA-associated uveitis

-

Inflammatory bowel diseases

-

Relapsing polychondritis

-

Tuberculosis

-

Syphilis

-

Lyme disease

-

Viral (Cytomegalovirus, HIV, West Nile)

-

Intravenous immunoglobulins

-

Inhalation of methamphetamine

-

Cancer associated retinopathy

-

Oculocerebral lymphoma

Susac’s syndrome, Sjogren’s syndrome, Rheumatoid arthritis, Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Whipple’ disease, and Rickettsial diseases are some of the rare systemic associations.

Clinical characteristics:

The classic symptom of retinal vasculitis is a painless decrease in vision. Other symptoms may include floaters from accompanying vitritis, a blind spot from ischemia-induced scotomas, metamorphopsia (change in shape of an object) in case of macular involvement or altered color perception. Retinal vasculitis can also be asymptomatic.

Retinal examination typically reveals sheathing (a whitish-yellow cuff of material surrounding the blood vessel) of the affected retinal vasculature associated with variable vitritis (inflammatory cells behind the lens in the vitreous body). It involves noncontiguous portions of the vessel. Inflammation may involve retinal arteries, veins or capillaries, but peripheral venous involvement is commonly recognized 2. Arterioles are preferentially involved in syphilis 3,4. The location and appearance of vascular lesions may have a limited diagnostic utility. "Candle- wax drippings" seen as dense, focal, nonocclusive periphlebitis are associated with sarcoidosis, but its appearance is neither pathognomonic nor present in all patients with the disease. The occlusive phlebitis of Behçet’s syndrome tends to manifest in the posterior pole, although peripheral retinal vasculitis may occur. Presence of a choroiditis lesion (active or healed) underlying the retinal vessels is a common observation in vasculitis of tubercular origin 5. Additional evidence of ocular inflammation such as cells in the aqueous humor may accompany retinal vasculitis.

Narrowing of the retinal blood vessels, vitreous hemorrhage, and new blood vessel growth are present as complications of retinal vasculitis.

Diagnosis and testing:

The laboratory evaluation should be directed by a careful history and physical examination followed by targeted laboratory and radiological testing. Investigating a case of retinal vasculitis involves a tailored approach. Once a differential diagnosis is derived from a detailed history, ocular examination and a relevant systemic evaluation, only the specific tests are carried out. Random screening with full battery of tests is rarely productive and can be misleading.

Besides subjecting every patient of retinal vasculitis to fundus photography and fluorescein angiogram, we perform the following ancillary tests as and when indicated:

-

Optical coherence tomography

-

Ultrasonograhy

-

Indocyanine green angiography

-

Ultrasound biomicroscopy

Few laboratory studies that should be done in all patients with isolated retinal vasculitis are:

-

Full blood counts

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

-

Mantoux test

-

Chest X-ray to rule out sarcoidosis or tuberculosis (Computed tomography if required)

-

Syphilis serology (Treponema pallidumhemagglutination test)

When strongly suspecting a specific etiology, the following tests are ordered in relevance to the particular disorder:

-

Toxoplasmosis serology

-

HIV

-

Lyme disease serology

-

X-ray of sacro-iliac joint

-

C-reactive protein

-

Serum Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme

-

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing (B51 for Behcet’s disease, DR3 for SLE and A29 for birdshot retinochoroidopathy; Although Behcet’s disease is associated with the HLA-B51 locus, not all patients have this genotype3)

-

Rheumatoid factor

-

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

-

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)

-

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of intraocular fluids (suspected tubercular or viral etiology)

-

Vitreous biopsy (suspected intraocular lymphoma)

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

-

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis- cytology and cell count

A repeat evaluation and follow-up may be required in cases where laboratory test results do not yield any positive information. A large majority of cases still remain undiagnosed by the routinely available laboratory tests and continue to be labeled as idiopathic 2.

Certain tests such as liver function and renal function tests are ordered before initiating antimicrobial drugs or during the course of treatment before considering immunosuppressive therapy or while evaluating the adverse effects of some of the treating agents.

Management:

The treatment of retinal vasculitis depends on the detection of an associated condition, severity of the disease, and whether the process is unilateral or bilateral. The treatment of any type of uveitis has three main goals: to prevent vision-threatening complications, to relieve the patient's complaints and, when feasible, to treat the underlying disease6. Treatment of retinal vasculitis can be divided into three main aims: Suppression of inflammation, treatment of specific disease, if identified, and treatment of complications

Corticosteroids

They are the main stay of treatment in primary retinal vasculitis or those with underlying systemic vascular disease. Aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy is not indicated

for patients with asymptomatic vascular sheathing. In the absence of a specific infection, administration of corticosteroids helps to control the inflammation. Depending upon the severity and extent of the disease, oral prednisolone is started in a daily dose of 1 to 1.5mg/kg body weight of the patient. As the inflammation subsides, tapering of corticosteroids by 5-10 mg per week is begun within 2-4 weeks of initiating therapy. Once the eye is completely quiescent, the corticosteroids are further tapered by 2.5-5 mg over few weeks and then discontinued.

Periocular depot steroids may be given as posterior sub-tenon injections in cases of unilateral disease. They are more commonly employed in our clinic for complications like cystoid macular edema.

The normal response to the corticosteroid therapy may be interrupted by recurrence of vasculitis in which case the oral corticosteroids are hiked to a dose of 1.5 to 2 mg/kg/day. Relapse of intraocular inflammation usually occurs when tapering is too rapid. All patients are monitored for side effects and complications of corticosteroids [secondary glaucoma, posterior subcapsular cataract, increased susceptibility to infection (ocular or systemic), hypertension, gastric ulcer, diabetes, obesity, growth retardation, osteoporosis and psychosis) at every follow up visit.

Immunosuppressive agents

Immunosuppressive therapy is usually a treatment of last resort, but there is little evidence that it is beneficial for the long-term retention of vision in severe idiopathic

retinal vasculitis. The use of immunosuppressive agents in retinal vasculitis is generally reserved for patients with bilateral disease whose vision has fallen below 20/40 in the better eye. Occlusive vasculitis in patients with Behcet's syndrome is the one form of uveitis for which most authorities agree that immunosuppressive drugs are the treatment of first choice. They are best administered by an internist experienced in their use, with monitoring of treatment effect by an ophthalmologist, indicating the importance of a team approach. The ones commonly used in ocular inflammations include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (MTX), mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine.

Other indications of immunosuppressive therapy in retinal vasculitis may include chronic inflammation that is not responding to the primary conventional corticosteroid therapy; multiple relapses of inflammation, in the same or other eye, or both eyes; or intolerance or contraindications to systemic corticosteroids.

These agents are started after an informed consent from the patient. The clinician should discuss extensively with the patient regarding the risks of secondary malignancy and gonadal dysfunction. Before starting any immunosuppressive drug, all patients are evaluated to rule out contraindications to treatment, such as hemoglobin, blood cell counts (leucocytes and platelets) and abnormal liver or renal function tests. While receiving these medications, the patients are monitored every four weeks for laboratory tests including blood cell counts, bilirubin, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine.

Identification of non infectious systemic associations warrants initiation of specific therapy, besides the conventional corticosteroids. Management of some of the common specific causes of retinal vasculitis is discussed below.

Behcet’s disease:Behcet’s disease is a systemic immune-mediated vasculitis of unclear origin. Although the vasculitis associated with Behcet’s disease responds well to systemic corticosteroids that also delays the time to blindness in patients with posterior segment involvement, but it does not alter the long-term outcome7. Further, majority of patients with ocular Behçet’s disease present with multiple relapses of inflammation. The long-term consequences of corticosteroids are unacceptable and they are not always suitable as a monotherapy for maintaining remission of vasculitis due to adverse side effects. Often it becomes necessary to add immunosuppressive drug as a steroid-sparing agent.

Cyclosporine A (3–5 mg/kg/day) and Azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day) are known to effectively control intraocular inflammation, to maintain visual acuity, and to prevent onset or progression of eye disease in ocular Behcet’s disease6,8. Despite aggressive immunosuppressive treatment, the visual prognosis of ocular BD remains generally poor8. Recently, novel biologic drugs, including interferon-a and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-a-antagonists have been introduced in the treatment of ocular Behcet’s disease with very promising results and seem for the first time to improve the prognosis of the disease9,10. Unfortunately, these new drugs are very expensive and therefore they may be not universally available in countries with a low economic status.

Sarcoidosis:Retinal vasculitis in sarcoidosis is less common than anterior uveitis and vitreitis11. Systemic corticosteroids (Prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) are the mainstay of treatment. When associated panuveitis is also present, topical corticosteroid and cycloplegic are given. The oral corticosteroids are tapered over 8-10 weeks by 5-10 mg per week depending upon the clinical response, in consultation with the pulmonologist. Few authors have reported the use of low-dose Methotrexate (MTX) in refractory cases of panuveitis12.

Retinal vasculitis may be caused directly by various infectious agents; in the majority of such cases specific antimicrobial therapy is available. It may be an antibiotic, antiparasitic or an antiviral drug administered for appropriate duration, with or without corticosteroids.

Tuberculosis:Tuberculosis is a common cause of retinal vasculitis in our experience. Once a diagnosis of presumed tubercular vasculitis is made, 4-drug anti-tubercular therapy including Isoniazid- 5 mg/kg/day, Rifampicin-450 mg/day (if body weight<50 kg and 600 mg/day if body weight > 50 kg), Ethambutol 15 mg/kg/day, and Pyrazinamide 25-30mg/kg/day is initiated under the supervision of an internist, and continued for 3-4 months. Oral corticosteroids are administered in the standard dose of 1 mg/kg body weight per day, to be tapered depending upon the clinical response. The patients are monitored for any liver toxicity. Thereafter, Rifampicin and Isoniazid are used for another 9-14 months. Pyridoxine supplementation is given to all patients receiving anti-tubercular therapy till cessation of therapy. Anti-tubercular therapy has shown to significantly reduce recurrence of inflammation13.

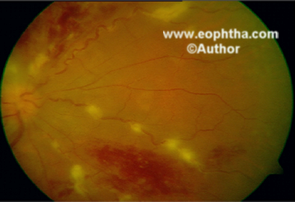

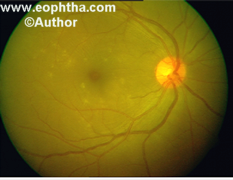

Figure 1a:Tubercular retinal vasculitis in a 26-year-old man. Note exuberant perivascular infiltrates both focal and segmental with extensive superficial flame shaped hemorrhages.

Figure 1b: Same eye as in figure 1a, 4 weeks after starting anti tubercular therapy and oral corticosteroids shows resolution of exudates and hemorrhages.

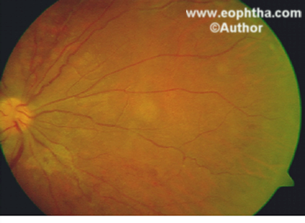

Figure 1c: Same eye as in figure 1a and 1b, 4 months later, shows almost complete resolution of retinal vasculitis

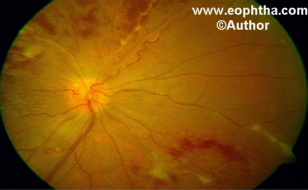

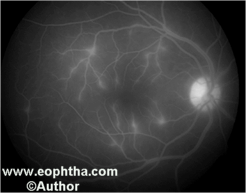

Figure 2a: A 40-year-old man with intraocular tuberculosis showing extensive inflammation of the upper and lower temporal vessels along with choroiditis. The lower temporal artery also shows perivascular exudates.

Figure 2b: Same eye as in figure 2b, 4 weeks later on anti tubercular therapy with corticosteroids shows resolution of inflammation. Retinal hemorrhages have absorbed to a great extent. Note deposition of hard exudates in fovea and resolving perivascular exudates especially around retinal arterioles.

Figure 2c: 3 months later, the eye shows resolution of all hemorrhages, and exudates. Note pigmented scar along upper temporal vessels from healing of the associated choroiditis. Healed choroiditis scars are typically seen in tubercular retinal vasculitis.

Toxoplasmosis:The most commonly used combinations are Clindamycin and corticosteroids; or Pyrimethamine, Sulfadiazine and corticosteroids. Oral corticosteroids are used to limit the damaging effects of inflammation. Recommended regimen includes tablet Clindamycin 300 mg four times daily (3-4 weeks) along with tablet Septran-DS 960 mg daily (960 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) for 3-4 weeks. Oral corticosteroids (1-1.5 mg/kg/day) are started 48 hours after starting antitoxoplasma therapy, and tapered according to the clinical response. Other drugs that have been used in ocular toxoplasmosis are Atovaquone and Spiramycin.

Syphilis:Penicillin remains the standard treatment for ocular syphilis. The recommended regimen for treatment of ocular syphilis is the same as that for neurosyphilis,i.e, intravenous crystal penicillin G 12–18 Million Units/day for 10–14 days, followed by supplementary intramuscular penicillin G 2.4 Million Units weekly for 3–4 weeks. If the patient is allergic to penicillin, then oral tetracycline 500 mg four times a day for 4-6 weeks is a good alternative.

Lyme disease:Lyme borreliosis greatly mimics syphilis and can cause false-positive readings on both specific and non-specific tests for syphilis. Patients with Lyme uveitis are treated as if they had neuroborreliosis. Intravenous therapy with either ceftriaxone, 2 g daily for adults (50 to 100 mg/kg/day for children) for 21 days; or penicillin G, 20 million units daily, or 0.25 to 0.5 million units/kg/daily for children. Doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily, is a good alternative in adults with less severe infection but contraindicated in children, pregnant or breastfeeding women. Some patients with severe ocular inflammation may require concomitant oral prednisone (0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) because of the possibility of paradoxical worsening (Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction). But steroids should not be used without appropriate antibiotic cover.

Surgical therapies such as laser photocoagulation or vitrectomy are generally not indicated except in the management of persistent neovascularization (new vessel growth) or in cases of bleeding into the vitreous or glaucoma., epiretinal membrane, tractional retinal detachment threatening the macula, combined tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and a densely opacified vitreous.

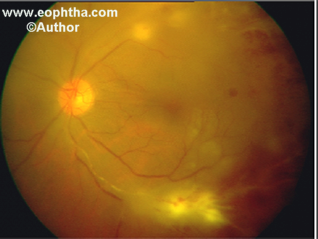

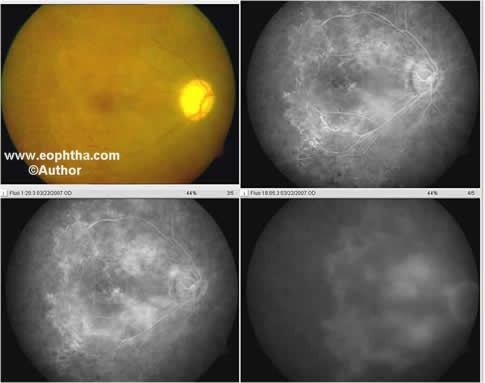

Figure 3a: A 19-year-old boy presenting with vitreous haze, and retinal infiltrates due to Behçet’s disease.

Figure 3b: Fundus fluorescein angiography of the same eye as in figure 3a shows perivascular staining of tertiary vessels in the macula. Note that points of intense focal staining on the angiogram correspond to the retinal infiltrates on the fundus picture in figure 3a.

Figure 4: A 25-year-old woman with advanced changes of Behçet’s disease in the right eye. On fundus fluorescein angiography, there was extensive retinal capillary non-perfusion and dye leakage from the remaining vessels in the posterior pole.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with retinal vasculitis is variable, reflecting the heterogenous nature of this group of disorders.

References:

-

Graham E, Spalton DJ, Sanders MD: Immunological investigations in retinal vasculitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1980; 101: 12

-

Sanders MD: Retinal arteritis, retinal vasculitis and autoimmune retinal vasculitis. Eye 1987; 1:441-465.

-

Morgan CM, Webb RM, O'Connor GR: Atypical syphilitic chorioretinitis and vasculitis. Retina 1984; 4:225-231.

-

Crouch ER, Goldberg MF: Retinal periarteritis secondary to syphilis. Arch Ophthalmol 1975; 93:384-387.

-

Gupta A, Gupta V, Arora S, Dogra MR, Bambery P. PCR-positive tubercular retinal vasculitis: Clinical characteristics and management. Retina 2001;21:435-44.

-

O¨zdal PC- , Ortac- S, Taskintuna I, Firat E. Long-term therapy with low dose cyclosporine A in ocular Behc- et’s disease. Doc Ophthalmol 2002;105:301–312

-

Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: Recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:492-513.

-

Deuter CME, Kotter I, Wallace GR, Murray PI, Stubiger N, Zierhut M. Behcet’s Disease: Ocular effects and treatment. Prog Ret Eye Res 2008;27:111-136.

-

Tugal-Tutkun I, Mudun A, Urgancioglu M, et al. Efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of uveitis that is resistant to treatment with the combination of azathioprine, cyclosporine, and corticosteroids in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 2478–84.

-

Ko¨ tter I, Gu¨ naydin I, Zierhut M, Stu¨ biger N. The use of interferon a in Behc- et disease: review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2004;33: 320–335.

-

Ganesh SK, Agarwal M. Clinical and investigative profile of biopsy-proven Sarcoid uveitis in India. Ocular Immunol and Inflamm 2008;16:17-22.

-

Shah SS, Lowder CY, Schmitt MA, et al. Low-dose methotrexate therapy for ocular inflammatory disease. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1419–23.

-

Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Bambery P, Arora SK. Role of anti-tubercular therapy in uveitis with latent/manifest tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2008 146;772-77