Introduction

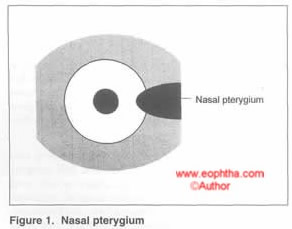

A pterygium is a fibrovascular, wing-shaped encroachment of the conjunctiva onto the cornea, usually in the horizontal meridian of the palpebral fissure. Histopathology shows hyaline degeneration with elastotic proliferation.

Risk factors

Exposure to ultraviolet light and environmental microtrauma to the ocular surface is thought to predispose to pterygium formation. A localized limbal stem cell dysfunction, possibly related to ultraviolet induced damage and a genetic predisposition has also been postulated.

Pathogenesis

Pterygium pathogenesis can be considered as occurring in two stages: the initial disruption of the limbal corneal-conjunctival epithelial barrier, and the progressive “conjunctivalization” of the cornea characterized by cellular proliferation, inflammation, connective tissue remodeling, and angiogenesis

Morphology

Head—the part which rests on the cornea

Neck— constricted portion seen at the limbus

Body – remaining bulk of mass

Cap—a semilunar infiltrating portion in front of the head showing opaque spots (Fuch’s spots) suggestive of progression.

STAGES

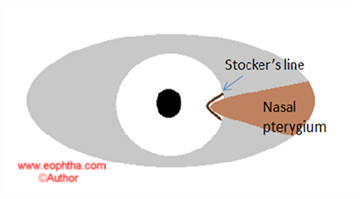

A progressive pterygium is thick, fleshy and vascular showing the presence of opaque infiltrates ahead of the head of the pterygium. A atrophic pterygium is thin, with little vascularity. The presence of a pigment line in front of the pterygium commonly referred to asStocker’s lineis suggestive of long standing non-progressive pterygium. A classification of the stage of pterygium based on the visibility of the underlying episcleral structures has been proposed.

PRESENTATION

Patients may present with repeated episodes of redness, pain, and watering due to inflammation of the pterygium, or due to drop in vision caused by encroachment of the pterygia onto the pupillary axis or high astigmatism. Quite often though, it may be an incidental finding in an asymptomatic patient.

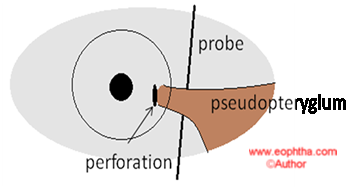

PTERYGIUM VS PSEUDOPTERYGIUM

A pseudopterygium is the result of corneal inflammation due to chemical burns, corneal perforation, or longstanding corneal ulcers, with the reparative process leading to the growth of the conjunctiva onto the cornea. It is differentiated from a true pterygium by the history of prior inflammation, presence in one eye, location other than the horizontal meridian, a configuration that does not resemble the “wing” structure of the true pterygium, non progressive nature, and the ability to pass a probe under the neck of the pterygium (in some cases).

What to look for?

-

Position : nasal or temporal

-

Laterality: true pterygia are usually bilateral as apposed to pseudopterygia.

-

Progression: increased vascularity and fleshiness is usually seen in progressive pterygia as apposed to thinned out pale atrophic pterygia.

-

Extent: of encroachment of the pterygia onto the cornea is required to predict outcome of intervention – especially with regard to vision recovery. The width of the pterygium at the limbus is also noted.

-

Presence of subepithelial deposits ahead of the head of the pterygia is suggestive of progression.

-

Presence of the Stocker’s line of pigmentation is suggestive of a long standing, non-progressive lesion.

-

Restriction of movement is often seen in recurrent pterygia with conjunctival loss and scarring.

-

Inflammation: the presence of conjunctival inflammation in the body of the pterygium should be noted.

-

In patients, who have a recurrent pterygium after previous surgery the presence of corneal thinning that may affect the surgical procedure, must be noted.

-

Similarly, if a conjunctival autograft is planned, the health of the bulbar conjunctiva, the presence of a glaucomatous bleb, and the possibility of future glaucoma risk in the patient, must be considered.

Treatment

The following are considered indications for the surgical treatment of a pterygium

-

Encroachment upon the pupillary area causing visual disturbance.

-

Recurrent inflammation.

-

Definite evidence of progression like - absence of Stocker’s line, subepithelial deposits ahead of the pterygium head.

-

Peripheral pterygium, but distortion of vision due to high astigmatism.

-

Restriction of ocular movement, with diplopia

-

Cosmetic reasons

-

Rarely, for suspicion of metaplastic changes.

MEDICAL

Patients who are at high risk of the development of pterygia because of a positive family history of pterygia or because of extended exposure to ultraviolet irradiation need to be educated in the use of ultraviolet-blocking glasses and other means of reducing ocular exposure to ultraviolet light such as avoid direct sunlight, wear goggles, cap, etc. The use of tear substitutes can be considered to minimize the effects of environmental microtrauma in those exposed to the same.

SURGICAL

1. Excision with simple closure of the wound.

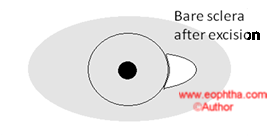

2. Mc Gavics bare sclera method: wherein the pterygia is excised and the conjunctival defect is left as it is.

3.Transplantation of the pterygia: done in recurrent pterygia/ large pterygia.

-

Mac Reynold’s operation: the head is sutured to the body itself

-

Kehr’s operation: the head is sutured to the inferior fornix

The bare sclera technique of pterygium excision was the preferred approach, until recently, owing to the simplicity of the procedure and short duration of surgery – often performed as an office procedure. Soon, however, came the realization, that the procedure resulted in unacceptably high rates of recurrence and granuloma formation – as high as 75 to 85% in some series. Hence, modifications of the procedure, described above, were introduced. Although these approaches increased the technical complexity of the procedure, the outcomes did not improve.

4. In order to reduce recurrence rates, the use of beta irradiation and thiotepa were considered to reduce the occurrence of the fibroblastic recurrence response.However the increased occurrence of scleral complications with these approaches, also reduced their applicability and these are also seldom in use today.

Current Surgical options:

-

Conjunctival-limbal autograft

-

Conjunctival autograft

-

Conjunctival rotational autograft

-

Mitomycin C

-

Mitomycin C + Conjunctival or Conjunctival-limbal autograft

-

Amniotic membrane transplantation

-

Use of fibrin glue with Conjunctival or Amniotic membrane transplants

-

Lamellar keratoplasty in conjunction with pterygium surgery

Surgical options for the Future:

1. Use of intralesional bevacizumab injections – as an adjunct to surgery

2. Bevacizumab eye drops or subconjunctival injections for treatment of recurrences

3. Conjunctival cultures on Amniotic membrane

Pterygium Excision With Conjunctival-Limbal Autograft

Rationale: Since alteration of the limbal cells is thought to incite the occurrence of pterygium limbal transplantation with conjunctival autograft is performed. The use of this technique has vastly improved the prognosis for pterygium surgery. It was introduced by Dr Kenneth Kenyon, and has been used by the authors, with good success, from the mid 1990’s in India. (Rao SK et al, Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1997 Oct;28(10):875-7)

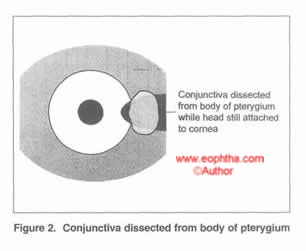

Pterygium excision can be done from its head or from its body. In general primary pterygia are easier to peel of the sclera since the adhesions are far less in comparison to recurrent pterygia. The author prefers excision from the head with conjunctival and limbal autograft and has had least recurrence from the same. (Conjunctival-Limbal autografts for primary and recurrent Pterygia: Technique and results. Rao SK et al. Indian J Ophthalmology; 1998:46: 14: 203-209)

The caveats of the procedure are as follows:

-

Anesthesia: While extensive pterygia are best done using a peribulbar injection of anesthetic, it may also be possible to do them using topical anesthesia, with or without a subconjunctival anesthetic injection. In this regard, the use of lignocaine gel has been proven to be quite efficacious. (Rao SK et al, Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006 Jun;84(3):445)

-

Try to preserve as much conjunctiva as possible: A small incision is made in the conjunctiva just medial to the head of the pterygium, avoiding the obviously altered conjunctiva on the head of the pterygium. Tenting up the dissected conjunctiva and snipping the taut adhesions to the subconjunctival tissue makes this dissection easier as the head of the pterygium helps providing taction.

-

Removal of the pterygium: The corneal epithelium 2 mm ahead of the head of the pterygium is scraped off with a hockey-stick knife. The hockey-stick knife is then used to elevate the thickened epithelium off the underlying cornea. Once this plane is defined, the pterygium head can easily be avulsed using a combination of blunt dissection and traction. Residual fibrous tissue on the cornea is removed by sharp dissection with a No. 15 Bard-Parker blade.

-

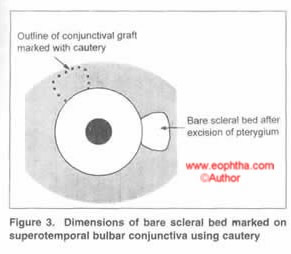

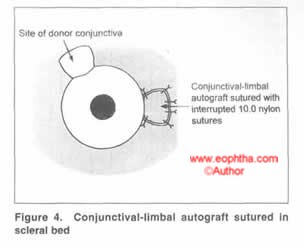

Conjunctival graft: The size of the conjunctival graft required to resurface the exposed scleral surface is determined using calipers in 3 directions - extent across the limbus, maximum circumferential extent of the bed, and maximum distance from the limbus. Care is taken to obtain as thin a graft as possible without button-holing. After excision, the conjunctival-limbal graft is slid onto the cornea. Without lifting the tissue off the cornea, it is rotated and moved onto its scleral bed with fine non-toothed forceps. A limbus-limbus orientation is maintained. The graft is secured using interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures, although vicryl sutures can also be sued with equal efficacy. (Rao SK et al, Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007 Sep;85(6):658-61). The four corners of the graft are anchored with episcleral bites to maintain position. The medial edge of the graft was sutured with 2-4 additional sutures.

-

Postoperative treatment: Topical steroids are used plentifully in the initial postoeprative period to reduce graft edema and improve graft survival. A typical course would be Q2H for 3 days, 6D for 2 weeks, 4D x 1 week, 3D x 1 week, 2D x 1 week, and 1D x 1week.

Inferior conjunctiva may also be used in a similar manner in cases where superior conjunctiva is to be preserved or is scarred. (Rao SK et al, Indian J Ophthalmol, 2000 Mar;48(1):21-4).

A similar procedure is used for a free conjunctival autograft as well – the excised graft does not include the limbal tissues.

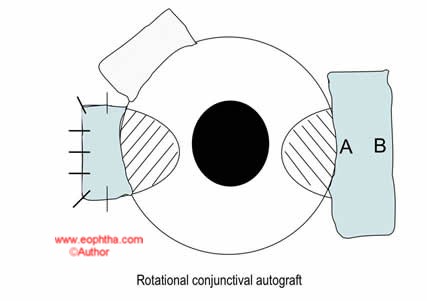

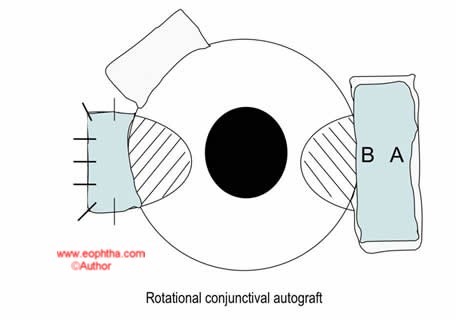

Conjunctival rotational graft with pterygia excision

This is indicated in some cases of double headed pterygia where enough conjunctiva may not be available to provide grafts for both sites of excision. It may also be considered in patients with associated glaucoma when preservation of the superior conjunctiva is advisable, or when there is significant superior conjunctival scarring, precluding conjunctival graft preparation.

In this procedure, the conjunctiva overlying the body of the pterygium is excised and placed in a bowl of saline. The pterygium is then excised and the conjunctiva is replaced in the bed – after rotating it 180 degrees, such that the limbal side now faces the fornix. The caveat in performing this procedure is to ensure that the initial excision of the conjunctiva extends well into the normal conjunctiva both above and below the body of the pterygium – as removing only the tissue on the body of the lesion results in tissue shrinkage and inadequate cover for the scleral bed.

Pterygium excision with mitomycin C (MMC)

Rationale:The use of MMC as an anti-fibroblastic agent is useful to help reduce fibroblast proliferation after pterygium excision. The use of MMC reduces surgical time. Although good results have been reported with its use, the possibility of scleral complications exists – even years after its use. Since abuse of MMC, when prescribed as postoperative drops has been described, it is generally preferable to use it during surgery.

Intraoperative use:

A mitomycin C (0.02%) soaked sponge is kept for a period of 3-5 min over the bare scleral bed – after pterygium excision and then washed off.

This may or may not be followed by a conjunctival autograft. Placing a graft gives the advantage of retaining some vascularity in the area and thus preventing occurrences of complications such as necrotizing scleritis postoperatively

Mitomycin C - 0.02%Available as 2 mg powder.

Add 10 ml normal saline solution = 0.2mg/ml (0.02%)

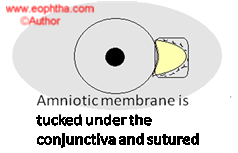

In the event of two-headed pterygia or very large pterygia with conjunctival loss amniotic membrane can be used to cover the defect.Pterygium excision with amniotic membrane transplantation

However, the use of this approach has been reported to have fairly high recurrence rates in most reported studies. In this context, it may be best to reserve the use of this approach in eyes that have had extensive removal of the conjunctiva, with an extensive defect, which may be hard to close with a conjunctival graft. In these instances, the use of an amniotic membrane graft can be considered to help reconstruct the ocular surface.

Fibrin Glue

The glue comes in two parts – a vial containing fibrinogen powder and another containing thrombin powder. The conjunctival graft is excised in the usual manner and is place stromal side up on the cornea, with the limbal edge adjacent to the limbus. After reconstituting the vials with the provided solutions and mixing them well – these are applied to the bed – this can be either done simultaneously using the modified syringe applicator provided or can be used as two separate solutions. If the latter, place the sticky fibrinogen in the scleral bed, and the liquid thrombin on the undersurface of the conjunctival graft. The graft is then flipped over into the bed and two fine-tipped forceps are used to stroke the graft to fit it into the bed. The edges of the graft are then coapted with the margins of the host conjunctiva to unite the edges of the graft with the margins of the conjunctival bed. Since fibrin formation occurs over 45 seconds, there is enough time to perform these maneuvers.

Lamellar Keratoplasty

When extensive corneal scarring in the visual axis coexists with the pterygium, a lamellar corneal graft is required along with pterygium excision and adjunctive procedures to improve vision.

Combination Approach

In very extensive pterygia, often recurrent, with significant conjunctival loss, it may be necessary to combine the above approaches – using extensive pterygium excision, with a conjunctival autograft, amniotic membrane transplant and intraoperative MMC. This may or may not need to be combined with a lamellar corneal graft for vision restoration.

Pterygium subconjunctival Avastin injection

Rationale: As pterygium is a fibrovascular proliferation, its growth requires new vessel formation. It is hypothesized that increased angiogenic inhibitors may regulate the formation and progression of pterygia. Studies have been done using bevacizumab 2.5mg/0.1ml injected at the limbus at the head of a possible recurrence. More than one injection may be required. Subconjunctival bevacizumab results in a short-term show a decrease in vascularization and irritation. Further long-term studies are needed to investigate the efficacy of bevacizumab as an adjunct to surgical excision or in combination with topical treatment.

Complications

1. Intraoperative problems: Globe rupture during the peribulbar block, damage to the rectus muscle, and intraocular penetration during graft suturing have been reported. Excessive corneal tissue removal during pterygium head removal and perforation can also occur.

2. Recurrence: is the most important complication of pterygium surgery. Fortunately, with well-performed surgery using the options mentioned above, recurrence rates can be as low as 3.8%. Recurrences can be of two types – across the graft, if the graft used is not viable; or around the graft – if inadequate excision of the pterygium and or a small graft is used.

3. Graft problems: include too large or too small a graft, buttonhole in the graft, improper suturing leading to an unsecured graft on the sclera, inversion of the graft with the epithelial side placed facing the sclera, and a large hematoma under the graft preventing a graft take.

4. Infection: as with any surgery, this can happen in pterygium surgery. can occur if complete excision of the pterygium is not done. Since corneal epithelial injury occurs during surgery, the infection can occur in the cornea, sclera, or both.

5. Granuloma: Usually seen after bare sclera surgery, the granuloma can occur in the scleral bed, or in cases of a conjunctival autograft, can occur at the site of donor graft excision, if the Tenon’s there is hydrated and does not get covered with conjunctiva in the healing period.

6. Surgically induced necrotizing scleritis: has been reported. Scleral melts after the use of MMC have also been reported.

7. Strabismus: recurrent pterygia may be difficult to dissect and damage to the rectus muscle may result in strabismus.

8. Diplopia: can result from cicatrizing changes in the conjunctiva after excision, affecting free movement of the eye.

9. Vision changes: from the corneal irregularity that can occur after pterygium removal from the cornea.

10. Steroid-induced IOP rise: is a problem in some patients, who are steroid responders.