1. Obtain a detailed history:

a. A history of injury and the injuring agent -some pointers from this would be the occurrence of fungal infections in injuries with vegetable matter/insect wing cases; bacillus infections in patients with broomstick injuries; gram-positive infections with metal foreign bodies and so on

b. A history of past such similar episodes -typically, this suggests the possibility of viral infections

c. History of contact lens use -in such cases, while there is the possibility of a sterile infiltrate, especially if such infiltrates are present at 3 and 9 o? clock periphery, it is imperative to keep in mind serious infections such as pseudomonas

d. Prior treatment history -obtain a detailed history of the name of antibiotic used, the frequency of use suggested, and the compliance of the patient with therapy. Failure to respond to adequate dose and duration of appropriate antibiotics suggests the possibility of a fungal or parasitic infection.

e. Pain, discharge, rapidity of progression -these details provide an idea of the virulence of the infecting agent, and determine the type of treatment response that is needed to protect the eye.

f. Steroid use / Past corneal disease -the use of topical steroids for other conditions and the presence of preexisting corneal disease predisposes the eye to infections - often by commensals of the ocular surface due to a compromise of ocular surface immunity.

g. Diabetes mellitus / Leprosy / other immunocompromised states / preexisting lacrimal sac disease- these again predispose the eye to infections, and the presence of constant watering of the eye prior to the present episode of corneal infection should arouse a suspicion of lacrimal sac disease, in which case pneumococcal infections should be suspected.

2. Examination

Signs

a. The extent of ocular inflammation and discharge -the presence of lid swelling, inability to open the eyes, a severe intolerance to light, the nature and type of discharge, the presence of conjunctival redness, and chemosis are pointers to the severity of the infection. The general rule is that in bacterial infections, the symptoms are more than the signs, and vice versa in fungal infections. Pale chemosis is typical of allergic conjunctivitis - and in the case of severe vernal conjunctivitis, it can be associated with a superior corneal epithelial defect, shield ulcer, or infective keratitis. Localized congestion and an ulcer very close to the limbus - especially if it is inferior and associated with similar-sized peripheral scars suggestive of past episodes, should alert the examiner to the possibility of phlyctenular keratitis.

b. Epithelial defect, size, and shape -The epithelial defect in infective keratitis is often obvious but sometimes may require fluorescein staining to detect the entire extent. In active bacterial keratitis, the epithelial defect is often larger in size than the infiltrate and a reduction in the size of the defect on the daily exam is commensurate with healing. However, in fungal keratitis, due to the compact nature of the underlying stroma, even in moderately advanced disease, the epithelial healing can progress well, and the size of the defect can be smaller than the extent of the infiltrate even in an eye with active disease. The dimensions of the ulcer should be measured in the longest axis and the meridian 90 degrees opposite. This can easily be done using the caliper on the illumination arm of the slit lamp - but care must be taken to place the illumination arm at 0-degree position when measuring dimensions. If the axis is shifted to the side, then depending on the position, a parallax error can be induced when making the measurement. The shape of the epithelial defect and the characteristic appearance should be noted. Terms such as a “string of pearls” - referring to multiple pinhead-sized infiltrates adorning the edge of the defect should be used only if Nocardia infection is suspected. Similarly, the use of the term “hyphate” to describe the edge of the defect indicates that the examiner is leading to a diagnosis of a fungal infection. A “cracked windshield” appearance indicates a possible mycobacterial infection. In bacterial infections, the use of the term “rounded” to describe the edge, suggests that the defect is healing - actively progressing ulcers have an “amoeboid” or “fimbriated” edge - essentially signaling irregularity and activity with a potential to spread.

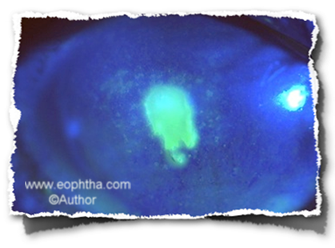

c. Infiltrate size, depth, thinning -As mentioned earlier, there can be a difference in the extent of the epithelial defect and the corneal infiltrate, and hence the infiltrate dimensions must be measured separately. The depth of the infiltration must be noted - superficial, mid, deep, or total corneal stromal thickness involvement. The presence of pigment in the infiltrate is a sign of fungal keratitis. A dry-looking infiltrate is more likely to be fungal, although, with virulent filamentous fungi, a rapidly progressing “wet” ulcer is also possible. The presence of corneal thinning or descemetocele formation must be carefully looked for. Such thinning is best avoided when performing a corneal scrape and if extensive, maybe an indication for adjunct surgical procedures like corneal glue application to protect the tectonic stability of the cornea. In an infiltrate covered ulcer, where is often difficult to see the area of thinning, possible clues are the presence of radiating striae in the surrounding Descemet's membrane.

d. AC reaction, hypopyon, rubeosis -the presence and extent of AC reaction indicates the severity of the keratitis. The height of the hypopyon is similarly a clue as to the activity of the disease. An active or fresh hypopyon is whitish in color, has a convex upper border, and is relatively fluid. Measuring these parameters will help in assessing the response of the patient to treatment. Looking carefully at the pupillary border for rubeosis can indicate the chronicity of the disease and the extent of inflammation.

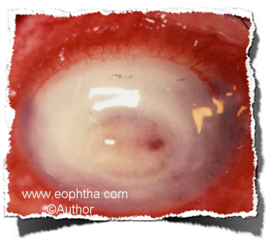

e. Specific signs -these are signs that are associated with specific infections - classical dendrites in herpes simplex or zoster keratitis, with simplex dendrites more likely to be single, central, long with thin branches, terminal bulbs, central gutter and therefore dual staining with fluorescein and rose bengal, and the associated skin lesions if present need not follow a dermatomal distribution with a midline demarcation. However, some early fungal hyphate lesions can mimic dendrites, as can early acanthamoeba keratitis. Pneumococcal ulcers are serpiginous with one healing edge trailing the active edge. Fungal lesions can have satellite lesions surrounding the main infiltrate. Acanthamoeba keratitis can show infiltrates along the nerves, and this is called radial keratoneuritis. Pseudomonal lesions have a rapid melting of the corneal stroma with copious, tenacious, sticky, greenish-yellow discharge.

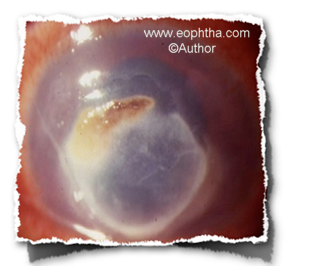

Fig: Fungal keratitis with pigment

Fig: Rapidly progressing bacterial infection with descemetocele

Fig: Radial keratoneuritis in acanthamoeba keratitis

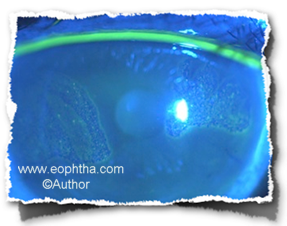

Fig: Mycobacterial keratitis in LASIK interface

f. Sensation, Lymph nodes, IOP, Posterior segment -Do not forget to check corneal sensation, the presence of regional lymph nodes - mostly preauricular, although submandibular and postauricular can also be involved. The IOP can be elevated in chronic infections - due to the anterior uveitis, possible peripheral anterior synechiae, and a pupillary block, and must be evaluated. Since contact tonometry in the presence of corneal infection is not advisable, either a non-contact measurement or digital tonometry can be performed. The posterior segment must also be assessed to complete the eye exam, and in severe infections, a B scan ultrasound may be required.

Fig: Viral dendrite

Once the presentation has been completed, the examiner will often ask the presenter to “summarize” the important findings in “one sentence”

This is a skill that needs to be practiced - but there are certain key elements in the construction of the sentence that can be planned before hand - common to all cases

A 66-year-old agricultural worker, diabetic under good control for the past 6 years, presents with increasing pain, redness, watering, and decreased vision in his right eye since 4 days, after trauma with a tree branch, despite treatment with moxifloxacin eye drops 6 times daily, and examination reveals moderate circumcorneal congestion, a central 4 x 3 mm epithelial defect with hyphate edges, 5 x 4 mm midstromal infiltrate, 2+ ?are and cells, 1 mm hypopyon, digitally normal IOP, normal corneal sensation, negative ROPLAS (regurgitation on pressure over the lacrimal sac - to look for chronic dacryocystitis) and no regional lymphadenopathy.

Essentially, this is a synopsis of all the segments we discussed in detail earlier.

The key elements in the construction of the sentence include -

Patient demographics - general health - symptoms - duration - progression - inciting factor(s) - prior treatment - findings : defect, infiltrate, AC reaction, hypopyon - IOP - sensation - ROPLAS - regional lymph nodes

Once this is done, the next question the examiner will usually ask is - Your diagnosis

Obviously, what can be offered here is a Provisional / Differential Diagnosis

Fig: Viral disciform keratitis

Fig: Active bacterial keratitis

Fig: Chronic keratitis - undeterminable morphology

The elements that help make the diagnosis are as follows

a. Bacterial -Contact lens use, symptoms more than signs, rapid progression, response to antibacterials, unifocal lesion

b. Fungal -Vegetable matter trauma, signs more than symptoms, morphology, dry lesion, satellites, sometimes pigment, and lack of response to antibacterials

c. Viral -dendrites, past history, old scars of herpes zoster, corneal sensation loss, possible regional nodes

d. Acanthameba -contact lens (although this is not often seen in India), pain, neural infiltrates, upper lid edema, waxing, and waning course

e. Atypical bacteria -indolent lesions, prior corneal surgery, morphology, failure to respond to usual antibacterial therapy, and slow progress

f. Microsporidiosis -presents as superficial punctate keratitis in immunodeficient patients and as necrotizing stromal keratitis in an immunocompetent patient - although recent reports suggest that this need not always be the case.

Based on the findings in the case in question, it would be advisable to make a provisional diagnosis - as mentioned above. In patients with history and findings that are equivocal, it may be better to hedge and provide a differential diagnosis - stating which findings are in favor of the differentials mentioned.

The next question will often be - how will you confirm the diagnosis?

The answer to this - I would do microbiological investigations - ideally a corneal scraping for smears and cultures. A blood sugar exam to rule out diabetes, and if needed, syringing to rule out chronic dacryocystitis.

Fig: Microsporidial keratitis

Smears - The procedure:

i. Done under topical - use proparacaine, as it is the least bacteriostatic

ii. In the OPD, with the patient seated at the slit lamp

iii. Gloving not necessary, and a wire speculum is optional

iv. Explain procedure to patient

v. Hold lids wide apart with the left hand, and use a sterile 15 BP blade for scrapes

vi. Obtain scrapes gently, but firmly from the edges of the keratitis

vii. Avoid obvious discharge and slough as they provide little useful information

viii. The material obtained is smeared on clean glass slides

ix. Once enough material is obtained - discard the now contaminated blade

x. Use a fresh blade to obtain material for cultures

Whether to use the initial scrapes (believed to have the highest yield of microorganisms for smear or culture is a controversy). Most microbiologists would like this to be used for the cultures as they place most reliance on this method of isolating the organism. For the clinician, however, the smear result is more important as it allows the determination of the initial antibiotic therapy in the clinic, rather than having to wait 48 to 72 hours for the culture to provide guidance.

Smears

-

Gram stain

-

KOH stain

-

Giemsa, if available

Cultures

-

Blood agar

-

Sabouraud's agar without cycloheximide

-

Brain Heart Infusion Broth

The above constitutes a basic profile. If required, this can be expanded

Smears

-

Acid Fast stain - Mycobacteria

-

Hanging drop - for acanthamoeba

-

Calcofluor white - for acanthamoeba

-

Gomor' s methenamine silver - fungus

Cultures

-

Chocolate agar - Neisseria

-

MacConkey's agar

-

Lowenstein Jensen slope - mycobacteria

-

Non Nutrient agar with heat-killed E Coli overlay - Acanthamoeba

For Viruses

-

Fluorescent antibody test

-

PCR

-

Culture

PCR tests are now available for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacteria as well, but these are usually performed in low-yield situations like vitreous or aqueous taps for endophthalmitis and not for corneal ulcers.

In general, it is important to be aware of the tests and the methods to do them - especially the stains.

Also, take care to remember the classificationof the organisms and the examples

a. Bacteria - Gram-positive cocci and bacilli; Gram-negative cocci and bacilli

b. Fungi - Filamentous (septate and aseptate), Yeast, Dimorphic / Pigmented c. Mycobacteria - Typical and atypical

Treatment:

Be aware of the common agents available for therapy

Gram-positive bacteria - Cephalosporins, Fourth generation fluoroquinolones, Vancomycin

Gram-negative bacteria - Fourth generation fluoroquinolones, amikacin, newer cephalosporins

Fungi - Natamycin, Amphotericin, Fluconazaole, Itraconazole, Voriconazole

Viruses - Acyclovir, Idoxuridine, Ganciclovir

Acanthamoeba - Polyhexamethylene biguanide, propamidine, chlorhexidine, Neosporin

Mycobacteria - Clarithromycin, fourth-generation FQs, Amikacin, Cephalosporins

Nocardia - Bactrim, Cephalosporins, fourth-generation FQs, Ampicillin

.jpeg)