It is a congenital ocular disorder where fetal vasculature persists. It can be either subtle (no disturbance in vision) or severe (profound visual loss)

Anatomy

The fetal vasculature is composed of two parts:

- Tunica vasculosa lentis: It is situated anteriorly encircling the lens. It has anterior and posterior divisions. Anterior division has additional attachments to the pupillary frill of the iris. Posterior division has additional attachments to the ciliary process and continues with the hyaloid artery posteriorly.

- Hyaloid artery: It is situated porteriorly behind the lens. It is also called primary vitreous. The hyaloid vessel extends from posterior surface of lens to the disc. The vasculature fills the vitreous cavity & has many attachments to the retinal surface

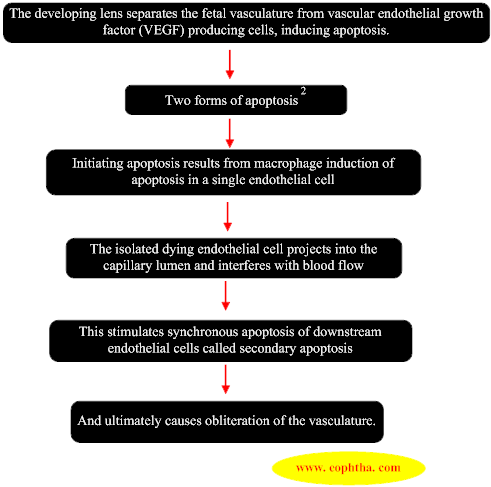

Normal regression of embryonic vascular system1

During development blood flow to the eye is through hyaloid artery. At the 240-mm stage (seventh month), blood flow in the hyaloid artery ceases. Hyaloid vascular regression occurs in following manner:

The developing lens separates the fetal vasculature from vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) producing cells, inducing apoptosis.

Pathologies of the Primary Vitreous1

The persistence of the hyaloid vascular system occurs in 3% of full-term infants and in 95% of premature infants. There is a spectrum of disorders resulting from the persistence of the fetal vasculature.

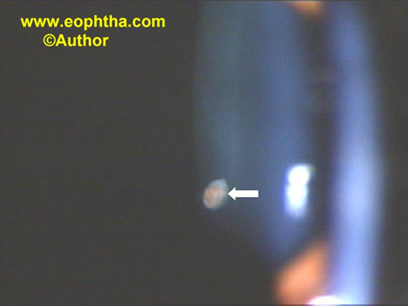

- Mittendorf s dotis a remnant of the former site of anastomosis of the anterior tunica vasculosa lentis and posterior hyaloid artery. It is usually inferonasal to the posterior pole of the lens and is not associated with any known visual dysfunction(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mittendorf’s dot (white arrow).

- Bergmeister's papillais the occluded remnant of the posterior portion of the hyaloid artery, associated with glial tissue. It appears as a gray, linear structure anterior to the optic disc(Figure 2). It also has no visual dysfunction.

Figure 2: Bergmeister's papilla (white arrow).

- Vitreous cystsare generally benign lesions that are found in eyes with abnormal regression of the anterior or posterior hyaloid vascular system. It can occur in otherwise normal eyes or eyes with coexisting ocular disease, such as retinitis pigmentosa, retinochoroidal colobomas and uveitis. Vitreous cysts are generally not symptomatic and thus do not require surgical intervention(Figure 3).

Figure 3: Vitreous cyst (white arrow) seen just behind the lens.

Persistent Fetal Vasculature Syndrome (PFVS)3,4

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV)

As mentioned earlier, it is a congenital ocular disorder in which fetal vasculature does not regress. It is unilateral approximately 90% of the time. No single gene has been identified. The new terminology for Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous(PHPV) is Persistent Fetal Vasculature Syndrome (PFVS).5 PFVS emphasizes not only the importance of both anterior tunica vasculosa lentis and posterior persistent hyaloid system but also represents the spectrum of structural changes which can present within the eye.

PFVS does not progress during the course of the child's life, but tractional intraocular changes can occur later, most likely due to eye growth. The stalk also can cause traction on the posterior lens capsule leading to posterior lenticonus. Traction on the ciliary body can lead to hypotony. Traction on the retina, leads to tractional retinal detachment.

There are three types of PFVS:

1. Anterior PFVS:

It has predominant features of persistent anterior tunica vasculosa lentis without much or any posterior hyaloid component.

Clinical features(Figure 4):

Figure 4: Anterior PFVS showing microphthalmos with cataract.

Clinical features (Figure 4):

- Presentation age 1 – 2 weeks after birth with leukocoria.

- Microphthalmos.

- Posterior lens opacity→ cataract.

- Retrolental fibrovascular membrane.

- Shallow AC→ glaucoma.

- Elongated ciliary process → hypotony.

- Stalk extending from posterior part of lens to optic disc may or may-not be present.

2. Posterior PFVS:

It has predominant features of persistent posterior hyaloid artery without much or any anterior tunica vasculosa lentis.

Clinical features:

- Microphthalmos (may or may-not be present).

- Posterior lens opacity.

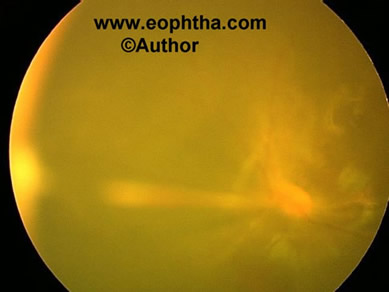

Figure 5: Posterior PFVS showing stalk extending from optic disc to lens.

- Vitreous stalk(Figure 5). The stalk can insert anteriorly on the lens either centrally, involving the visual axis or eccentrically, sparing the visual axis of the lens. If the stalk is eccentric, no change in visual acuity is noticed in the very young child, but strabismus can result. If there is a visual axis opacity, the problem usually is discovered at the newborn screening. The child with a stalk eccentric to the visual axis often presents with strabismus later in life, at age 9 to 10 months.6 Intrinsic retinal vessels can be pulled onto the stalk tissue and occasionally can be dragged one to two thirds the length of the stalk toward the lens. The surgeon should be aware of this as great care is required to divide only stalk tissue, not retina or intrinsic retinal vessels. This could lead to a retinal hole or bleeding, followed by a retinal ischemic event.

- Retinal fold.

- Tractional retinal detachment.

- Hypoplastic optic nerve & macula.

3. Mixed PFVS:

This occurs when both the tunica vasculosa lentis and hyaloid system is present. It has a spectrum of presentations depending on the degree of involution of the hyaloid and tunica vasculosa lentis.

Associated diseases

Other systemic associations have been reported with PFV syndrome, most often in association with central nervous system problems 9. However, many of these reports do not rule out mutations in the Norrie disease gene. Associations have also been reported with oculo-palatal-cerebral syndrome 10, intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection 11, intrauterine exposure to clomiphene, oral-facial-digital syndrome, anterior and posterior colobomas or even cystic globes 12,13 and tuberous sclerosis.14

Differential Diagnosis

- Retinoblastoma

- Norrie disease: When bilateral PFV syndrome is present8.

- Congenital cataract.

- Walker-Warburg syndrome.

- Trisomy.

- Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.

- Incontinentia pigmenti.

- Retinopathy of prematurity.

Visual prognosis

The severity of anterior segment appearance, globe size, severity of lens involvement or vascular appearance does notpredict the amount of retinal dysplasia, which in turn often determines the eye's visual result. Retinal dysplasia can be divided into macroscopic and microscopic types.Macroscopic dysplasiais defined as changes easily visible with the operating microscope or indirect ophthalmoscope.Microscopic dysplasiaoccurs at the cellular or vascular level. Although at present we have no way to determine cell dysplasia, vascular dysplasia can be assessed by fluorescein angiography. An example of vascular dysplasia is the lack of a capillary-free zone. This finding can be missed without angiography and might account for some of the poor vision after successful surgery. Visual evoked potential testing may be useful in predicting retinal dysplasia.7 If a response is present, then it can be helpful in the decision whether to recommend surgery for retinal detachment. This is most helpful when the other eye is uninvolved, and the waveforms can be compared.

Investigations

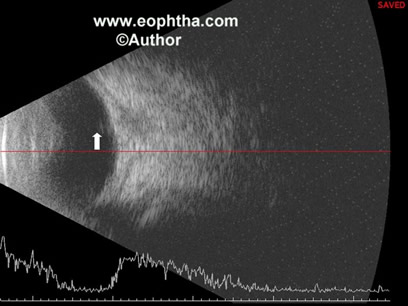

B scan ultrasound 15: Echography usually shows a shorter than normal globe, although it may be normal in some patients. The lens is often thin and there may be irregularity of the posterior capsule. A retrolental membrane can sometimes be demonstrated. A vitreous band (persistent hyaloid vessel) may be seen extending from the posterior lens capsule to the optic disc. Very often this band is extremely thin and difficult to identify along its entire course(Figure 6). In other situations, it can be extremely thick and easy to demonstrate. Sometimes a tractional retinal detachment can be seen posteriorly which can help to differente vitreous band from a closed funnel retinal detachment.

Figure 6: B scan photo showing a thin band (white arrow) extending aneriorly.

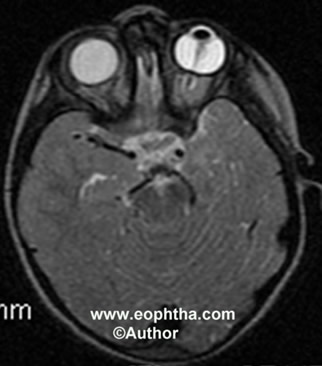

Computed tomographic scanning and magnetic resonance imaging(Figure 7)are rarely needed, mainly to rule out retinoblastoma in doubtful cases.

Figure 7: MRI scan showing stalk in the right eye.

Treatment3,4

The problem associated with PFVS can be divided into two components that affect vision: the media opacity and retinal changes (both dysplasia and traction). Media opacities are treated similarly to that of congenital cataract that is by lens removal, refraction and amblyopia management.

Anterior PFVS

- Standard three ports are made with infusion in ITQ

- Entry should be anterior (even through limbus)

- Lensectomy performed

- Lens zonules & opaque tissue are divided from the ciliary processes and removed.

- If dense cartilage tissue present, then it has to be removed through the limbus

- Diathermy is used to ablate the central vessel

- Stalk has to be managed next (if required)

Posterior PFVS

- Surgery not required if no traction present on

- Lens capsule

- Retina

- Not in visual axis

- Lens sparing vitrectomy is the surgery of choice.

- Entry is through pars plicata (as pars plana is still not developed in infants) 1.5 mm from limbus instead of 4 mm (as in adults) to avoid creation of itrogenic breaks.

- Lens occupies large portion of posterior segment and therefore may restrict intraocular manipulation and increase risk of mechanical damage.

- Intrinsic retinal vessels can be present in stalk

- Stalk is pushed from side to side before dividing to determine any retinal circulation alteration

- If this is present, it is better to leave a longer stalk

- Fine areas of organised vitreous support stalk

- It should be divided in such a way that it keeps the stalk from falling towards the centre of macula

- At the end fluid air exchange is done

Postoperative Treatment

- Surgery alone does not constitute treatment

- Aggressive management of amblyopia by way of contact lenses, aphakic glasses or PCIOL implantation is needed for a good visual outcome

Conclusion

- With modern vitreoretinal techniques, good visual results are possible

- However, this depends on

- Timing of intervention

- Anatomy of posterior pole

- Amount of anisometropia

- Amblyopia management

References

- Sebag J, Nguven N: Embryology of the posterior segment and developmental disorders. B. Vitreous embryology and vitreo-retinal developmental disorders. In: Hartnett ME, editor.Pediatric Retina. Philadelphia. Lippincott Willaims & Wilkins, 2005. pp 13-28.

- Meeson A, Palmer M, Calfon M et al. A relationship between apoptosis and flow during programmed capillary regression is revealed by vital analysis.Development1996;122:3929.

- Trese MT, Capone A Jr. Persistent fetal vasculature syndrome (Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous). In: Hartnett ME, editor.Pediatric Retina. Philadelphia. Lippincott Willaims & Wilkins, 2005. pp 437-443.

- Trese MT. Pediatric vitreous surgery. In: Peyman GA, Meffert SA, Conway MD, Chou F.Vitreoretinal surgical techniques. London. Martin Dunitz, 2001. pp 509-518.

- Goldberg MF. Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV): an integrated interpretationofsigns and symptoms associated with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV). LIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture.Am J OphthalmoI1997;124:587-626.

- Shaikh S, Trese MT. Lens-sparing vitrectomy in predominantly posterior persistent fetal vasculature syndrome in eyes with nonaxial lens opacification.Retina2003;23:330-334.

- Dass AB, Trese MT. Surgical resultsofpersistent hyperplastic primary vitreous.Ophthalmology1999; 1 06:280-284.

- DeJuan E Jr, Farr A, Noorily S. Retinal detachment in infants. In:Ryan SI, Wilkinson CP, eds.Retina,3rd ed., vo!. 3, Surgicalretina. St. Louis: Mosby, 2001:2501.

- Marshman WE, Jan JE, Lyons CJ. Neurologic abnormalities associated with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous.Can]OphthalmoI1999;34:17-22.

- Pellegrino JE, Engel JM, Chavez D. Oculo-palatal-cerebral syndrome: a second case (review).Am JMed Genet2001;99:200-203.

- Corey RP, Flynn JT. Maternal intrauterine herpes simplex virusinfection leading to persistent fetal vasculature.Arch Ophthalmol2000;118:837-840.

- Tsai PS, O'Brien JM. Retinal hamartoma in oral-facial-digitalsyndrome.Arch Ophthalmol1999;117:963-965.

- Pasquale LR, Romayananda N, Kubacki J, et a!. Congenital cystic eye with multiple ocular and intracranial anomalies.ArchOphthalmoI1991;109:985-987.

- MilotJ, MichaudJ, Lemieux N, et a!. Persistent hyperplastic ptimary vitreous with retinal tumor in tuberous sclerosis: reportofa case including tumoral immunohistochemistry and cytogenetic analyses.Ophthalmology1999; 1 06:630-634.

- Byrne SF, Green RL. Intraocular tumors. In: Byrne SF, Green RL, editors. Ultrasound of the eye and orbit. Second edition. St. Louis. Mosby, 2002. pp 115-190.