Lattice degeneration is a vitreoretinal degenerative process of the peripheral retina with visible lesions that predispose to retinal tears and detachment. Vitreous traction at sites of significant vitreoretinal adhesion is responsible for most retinal breaks that lead to retinal detachment.

GOALS of identifying the patients with risk of RD are:

- Identify patients at risk of RRD

-

Examine patients with symptoms of acute PVD to detect and treat significant retinal breaks

-

Manage patients at high risk of developing retinal detachment

-

Educate high-risk patients about symptoms of PVD, retinal breaks, and retinal detachments and about the need for periodic follow-up.

Natural history of precursors to rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

Precursors to retinal detachments are PVD, symptomatic retinal breaks, asymptomatic retinal breaks, lattice degeneration, and cystic and zonular traction retinal tufts. Because spontaneous reattachment is exceedingly rare, nearly all patients with asymptomatic RRD will progressively lose vision unless the detachment is repaired. Currently, more than 95% of RRDs can be successfully repaired, although more than one procedure may be required. The treatment of breaks/lattices before a significant detachment has occurred usually prevents progression, is uncomplicated and results in excellent vision. The early diagnosis of a retinal detachment is also important because the rate of successful reattachment is higher and the visual results are better if detachment spares the macula.1,2 Successful treatment allows patients to maintain their abilities to read, work, drive, care for themselves, and enjoy a better quality of life.3

Lattice Degeneration

Lattice degeneration can cause RRD by two mechanisms, including either round holes without PVD or tractional tears associated with PVD. Younger myopic patients who have lattice degeneration with round holes need regular follow-up visits, because they can develop small, localized retinal detachments, which occasionally slowly enlarge to become clinical retinal detachments. Treatment should be considered if the detachments are documented to increase in size.4,5

Generally, however, atrophic round holes within lattice lesions and minimal subretinal fluid do not require treatment. Byer studied 423 eyes with lattice degeneration in 276 patients over a period averaging almost 11 years.5 Of these, 150 eyes (35%) had atrophic holes in the lattice, and 10 of these 150 had subretinal fluid extending more than one disc diameter from the break. Six other eyes developed new subclinical retinal detachments during follow-up. Clinical retinal detachments developed in three of the 423 eyes.5 Two were due to round retinal holes in lattice lesions of patients in their mid-twenties and one was due to a symptomatic tractional tear. These data indicate that patients with lattice degeneration with or without round holes are not at significant risk of subsequent retinal detachment without a previous retinal detachment in either eye.

Retinal detachment usually occurs in eyes with lattice degeneration when a PVD causes a horseshoe tear, and such tears should be treated.4,5

Folk et al retrospectively studied 388 consecutive patients with lattice degeneration in both eyes who had phakic retinal detachment as a result of the lattice degeneration in one eye.6 In the second eye all areas of lattice degeneration were prophylactically treated by laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy in 237 eyes and 151 eyes received no treatment. During a mean follow-up period of 7.9 years, retinal detachment occurred in three treated eyes (1.8%) and in nine untreated eyes (5.1%). The clinical significance of this retrospective study of variable follow-up is uncertain.

Lattice Degeneration as a Risk factor

Lattice degeneration is present in 6% to 8% of the population and increases the risk of retinal detachment.5 Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with RRD have lattice degeneration.5

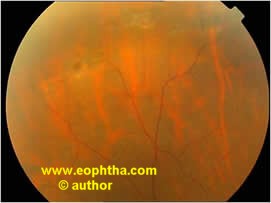

Fig: Laser marks around a lattice

Prevention and Early detection

There are no effective methods of preventing the vitreous changes that lead to RRD. If factors associated with an increased risk of retinal detachment are discovered during a routine eye examination in an asymptomatic patient, a peripheral fundus examination is advisable. Patients at high risk should also be educated about the symptoms of PVD and retinal detachment as well as about the value of periodic follow-up examinations.

Care process

Patient outcome criteria

In general, outcome criteria include the following:

-

Identification of patients at risk

-

Prevention of visual loss and functional impairment

-

Maintenance of quality of life

Diagnosis

The initial evaluation of a patient with risk factors or symptoms includes all features of the comprehensive adult medical eye evaluation, with particular attention to those aspects relevant to PVD, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration.

History

Patient history should include the following elements:

-

Symptoms of PVD – flashes and floaters

-

Family history

-

Prior eye trauma

-

Myopia

-

History of ocular surgery, including refractive lens exchange, lasik and cataract surgery

Examination

The eye examination should include the following elements:

-

Peripheral fundus examination with scleral depression

-

Examination of the vitreous for hemorrhage, detachment, and pigmented cells

There are no symptoms that can reliably distinguish a PVD with an associated retinal break from a PVD without an associated retinal break; therefore, a peripheral retinal examination is required. The preferred method of evaluating peripheral vitreoretinal pathology is with indirect ophthalmoscopy combined with scleral depression. Many patients with retinal tears have blood and pigmented cells in the anterior vitreous. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy with a mirrored contact lens or a small indirect condensing lens may complement the examination.

Diagnostic Tests

If it is impossible to evaluate the peripheral retina due to vitreous hemorrhage, B-scan ultrasonography should be performed to search for retinal tears or detachment and for other causes of vitreous hemorrhage. If no abnormalities are found, frequent follow-up examinations are recommended.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to create a firm chorioretinal adhesion with cryotherapy or laser photocoagulation in the attached retina immediately adjacent to and surrounding the retinal tear and/or the focal accumulation of subretinal fluid associated with the break/lattice.

Treatment of peripheral horseshoe tears should be extended well into the vitreous base, even to the ora serrata. The most common cause of failure in treating horseshoe tears is failure to treat far enough anteriorly. Continued vitreous traction can extend the tear beyond the treated area, allowing fluid to leak into the subretinal space and cause a clinical retinal detachment. Treatment of dialyses must extend over the entire length of the tear, reaching the ora serrata at each end.

There is insufficient information to make evidence-based recommendations for management for other vitreoretinal abnormalities. In making the decision to treat other vitreoretinal abnormalities, including lattice degeneration and asymptomatic retinal breaks, the risks that treatment will be unnecessary, ineffective, or harmful must be weighed against the possible benefit of reducing the rate of subsequent retinal detachment. Table 1 summarizes recommendations for management.

The surgeon should inform the patient of the relative risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery. The surgeon is responsible for formulating a postoperative care plan and should inform the patient of these arrangements.

Retinal detachments may occur in spite of appropriate therapy. Traction may pull the tear off the treated area, especially when breaks are large or have bridging retinal blood vessels, because the treatment adhesion is not complete for up to 1 month. Furthermore, 10% to 16% of patients will develop additional breaks during long-term follow-up. Pseudophakic patients are more likely to require retreatment or to develop new breaks.

TABLE 1 MANAGEMENT OPTIONS |

|

|

Type of Lesion |

Treatment |

|

Acute symptomatic horseshoe tears |

Treat promptly |

|

Acute symptomatic operculated tears |

Treatment may not be necessary – but better to treat |

|

Traumatic retinal breaks |

Usually treated |

|

Asymptomatic horseshoe tears |

Usually can be followed without treatment – but better to treat |

|

Asymptomatic operculated tears |

Treatment is rarely recommended if small. Treated if large and associated with other vitreo-retinal pathologies |

|

Asymptomatic atrophic round holes |

Treatment is rarely recommended |

|

Asymptomatic lattice degeneration without holes |

Not treated unless PVD causes a horseshoe tear or traction is noted at examination |

|

Asymptomatic lattice degeneration with holes |

Usually does not require treatment. But requires a close follow-up and patient should be educated about the signs and symptoms of RD |

|

Asymptomatic dialyses |

No consensus on treatment and insufficient evidence to guide management, hence better t treat |

|

Eyes with atrophic holes, lattice degeneration, or asymptomatic horseshoe tears where the fellow eye has had a retinal detachment |

No consensus on treatment and insufficient evidence to guide management, hence better to treat |

There is insufficient evidence to recommend prophylaxis of asymptomatic retinal breaks for patients undergoing cataract surgery.

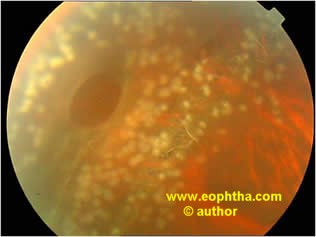

Fig: Pre & Post treatment photograph

Complications of Treatment

Epiretinal membrane proliferation (macular pucker) has been observed after aggressive treatment for PVD associated with holes/lattices/horse shoe tears, but it remains unknown whether treatment increases the risk of epiretinal membrane formation.

Followup

The guidelines in Table 2 are for routine follow-up in the absence of additional symptoms. Patients with new symptoms or a change in symptoms may require more frequent evaluation. Patients with no positive findings at the initial examination should be seen at the same intervals. All patients with risk factors should be advised to contact their ophthalmologist promptly if new symptoms such as flashes, floaters, peripheral visual field loss, or decreased visual acuity develop. Younger myopic patients who have lattice degeneration with holes need regular follow-up visits, because they can develop small localized retinal detachments that occasionally slowly enlarge to become clinical retinal detachments. Treatment should be considered if the detachments are documented to increase in size.

Patients presenting with acute PVD and no retinal breaks have a small chance of developing retinal breaks in the weeks that follow. Thus, selected patients, particularly those with any degree of vitreous pigment, hemorrhage in the vitreous or on the retina, or visible vitreoretinal traction, should be asked to return for a second examination within 6 weeks following the onset of symptoms.

TABLE 2 RECOMMENDED GUIDELINES FOR FOLLOW-UP |

|

|

Type of Lesion |

Follow-up Interval |

|

Symptomatic PVD with no retinal break |

Depending on symptoms, risk factors, and clinical findings, patients may be followed in 1 to 6 weeks, then 6 months to 1 year |

|

Acute symptomatic horseshoe tears |

1 to 2 weeks after treatment, then 4 to 6 weeks, then 3 to 6 months, then annually |

|

Acute symptomatic operculated tears |

2 to 4 weeks, then 1 to 3 months, then 6 to 12 months, then annually |

|

Traumatic retinal breaks |

1 to 2 weeks after treatment, then 4 to 6 weeks, then 3 to 6 months, then annually |

|

Asymptomatic horseshoe tears |

1 to 4 weeks, then 2 to 4 months, then 6 to 12 months, then annually |

|

Asymptomatic operculated tears |

2 to 4 weeks, then 1 to 3 months, then 6 to 12 months, then annually |

|

Asymptomatic atrophic round holes |

1 to 2 years |

|

Asymptomatic lattice degeneration without holes |

Annually |

|

Asymptomatic lattice degeneration with holes |

Annually |

|

Asymptomatic dialyses |

If untreated, 1 month, then 3 months, then 6 months, then every 6 months |

|

Eyes with atrophic holes, lattice degeneration, or asymptomatic horseshoe tears in patients in whom the fellow eye has had a retinal detachment |

Every 6 to 12 months |

Follow-up History

Patient history should identify changes in the following:

-

Visual symptoms

-

Interval history of eye trauma or intraocular surgery

Examination

The eye examination should emphasize the following elements:

-

Visual acuity assessment

-

Evaluation of the status of the vitreous, with attention to the presence of pigment, hemorrhage, or syneresis

-

Examination of the peripheral fundus with scleral depression

-

B-scan ultrasonography if the media are opaque

For treated patients, if the treatment appears satisfactory at the first follow-up visit, indirect ophthalmoscopy and scleral depression at 3 or more weeks will determine the adequacy of the chorioretinal scar, especially around the anterior boundary of the tear. If the tear and the accompanying subretinal fluid are not completely surrounded by the chorioretinal scar, additional treatment should be administered. At any postoperative visit, if subretinal fluid has accumulated beyond the edge of treatment, additional treatment should be considered.

Even if a patient has had adequate treatment, additional examinations are important. Between 5% and 14% of patients found to have an initial retinal break will develop additional breaks during long-term follow-up, and these percentages appear to be similar regardless of how the initial breaks were treated. New breaks may be particularly likely in eyes that have undergone cataract surgery.

Counseling/Referrals:

All patients at increased risk of retinal detachment should be instructed to notify their ophthalmologist promptly if they have a substantial change in symptoms, such as an increase in floaters, loss of visual field, or decrease in visual acuity. If patients are familiar with the symptoms of retinal tears or detachment, they may be more likely to report promptly after their onset, increasing the chances for successful surgical and visual results. Patients who undergo refractive surgery to reduce myopia should be informed that they remain at risk of RRD despite a reduction of their refractive error.

REFERENCES

1. Tani P, Robertson DM, Langworthy A. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment without macular involvement treated with scleral buckling. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;90:503-8. 2. Benson WE, Grand MG, Okun E. Aphakic retinal detachment. Management of the fellow eye. Arch Ophthalmol 1975;93:245-9. 3. Scott IU, Smiddy WE, Merikansky A, Feuer W. Vitreoretinal surgery outcomes. Impact on bilateral visual function. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1041-8. 4. Byer NE. Rethinking prophylactic therapy of retinal detachment. In: Stirpe M, ed. Advances in Vitreoretinal Surgery. New York, NY: Ophthalmic Communications Society, 1992. 5. Byer NE. Long-term natural history of lattice degeneration of the retina. Ophthalmology 1989;96:1396-401; discussion 1401-2. 6. Folk JC, Arrindell EL, Klugman MR. The fellow eye of patients with phakic lattice retinal detachment. Ophthalmology 1989;96:72-9.